Malaysia, an economy tipped to reach high income status by 2024. Historically a commodity exporter, Malaysia’s economy is now a manufacturing hub. Though, how did Malaysia’s economy get to this stage.

Why has it been stuck in the middle income trap for so long and what could be the solution?

To understand all of this, we first need to take a look at Malaysia’s history.

What Did Malaysia’s Economy Look Like At Independence?

Following independence from the British in 1957, Malaysia inherited an economy focused on producing commodities for export, particularly, rubber and tin.

The nation’s infrastructure – everything from ports to roads and railways, was all geared towards an economic model which exported raw materials and imported manufactured goods, with over 90% of exports in 1960 being either agricultural or mining commodities.

Now, just like any economy, Malaysia’s geography has and does play an important role.

The nation is essentially split between the Malay Peninsula and Malaysia’s provinces on the Island of Borneo. The vast majority of people though, about 80%, work and live on the Western peninsula making it the hub of Malaysia’s economy but also highlighting some of the geographical challenges the nation faces.

This skew in its population was somewhat encouraged by the colonial administration but the concentration of people and exports wasn’t the only legacy.

Over the decades, a significant number of migrants particularly from China and India had made their way to Malaysia, explaining why they make up over a quarter of the population today.

Historically, certain segments of these groups had certain economic advantages. And this is important, as following independence, the country’s economic policies have tried to ensure development is more evenly distributed as racial tensions had been a factor in the expulsion of Singapore from Malaysia.

To address this, the nation launched the New Economic Policy which aimed to reduce social tensions by reducing economic disparities – through offering more economic opportunities and support to the nation’s population. A factor that has set the tone throughout Malaysia’s development path.

How Did Malaysia Develop From Low to Middle Income Status?

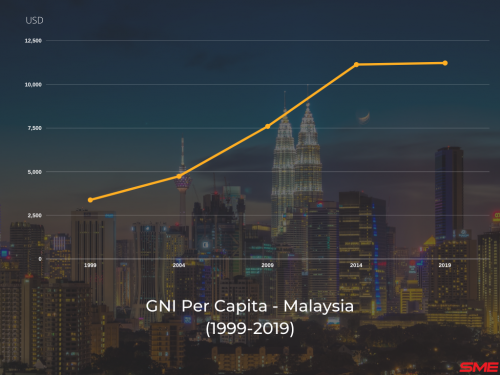

It’s important to highlight, that, as you are reading this today, Malaysia has already made good economic progress. Growing its gross national income per capita more than three times over the last 20 years.

Source: World Bank

Sure, this isn’t Singapore-style growth, yet, a lot of work has already been done to become a high-income nation.

One of the very first things Malaysia did after independence, was shift away from commodities to higher value manufacturing. And this makes sense, as agricultural based industries are typically less productive, attracting lower wages, and offering limited improvements to skill sets.

This was partly achieved through export-orientated policies, as well as the gradual removal of barriers to imports. For example; between 1970 and 1987, taxes on industrial chemicals were reduced from 160% to 16% and tobacco from 125% to 26%.

The other key part of this change, was how involved the government became in industrialization.

Malaysia saw how other Asian nations – first Japan and then South Korea had managed to develop their economies based on a state-led development model. Becoming convinced that their path to riches laid in adopting similar strategies.

So, the government turned its economic focus towards state-owned industries, and an excellent example of this was the Heavy Industries Corporation of Malaysia (HICOM), which set up heavy industries like steel and automobile manufacturing on the basis of government protection.

This company sprawled into a huge conglomerate, employing tens of thousands of people and owning hundreds of companies. The success of this strategy is perhaps best highlighted by the fact that Malaysia launched its very own national car brand Proton.

You see, just like other countries, the government thought there was no better way to showcase its industrial prowess than through the ultimate symbol of manufacturing: the automobile.

Despite more recent failures, which are beyond the scope of this article, Proton was a success for a time. At one point, seven out of every ten cars sold in Malaysia, were Proton’s and it even went on to achieve international awards.

A key reason for this success was because the government encouraged heavy industry to set up joint ventures particularly with other Asian companies, part of the government’s look East agenda.

In Proton’s case, this was with Japan’s Mitsubishi Motors, being a great example of a wider strategy Malaysia used to develop, especially its industrial base, through a heavy reliance on multinational corporations setting up manufacturing plants to capitalize on the nation’s comparative advantage in cheap labor. A strategy we have discussed before for a lot of countries.

Though, to be fair by the 90s, the country had realized that state-led development may not have been such a great idea. Yes, it could enable industries to grow under state protection and help shift the overall economy towards industrialization, but it didn’t necessarily make these enterprises competitive, especially in the long term.

So, a lot of the government shares in these enterprises were privatized. With the proceeds of this privatization being used to help set up the nation’s very own sovereign wealth fund, which nowadays, acts as a more market-oriented investment arm for viable local enterprises, being the 35th largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.

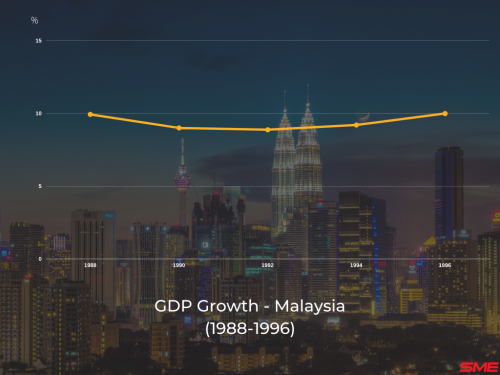

However, stating all of these, by the 90s, Malaysia’s economic model was still heavily dependent on inflows of foreign capital, which had seemed to serve the economy very well, averaging 9% growth between 1988 and 1996, with the country being compared to other Asian tiger economies.

Source: World Bank

But, this economic strategy had made the economy very vulnerable to the flows of international capital markets leading to the creation of a bubble in its housing and stock markets. And inevitably, just like any bubble, this burst, crashing down with the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997.

And this was the crisis which didn’t even start in Malaysia, but in neighboring Thailand over speculation that its currency was overvalued. However, this quickly spread to Malaysia and other economies in the region.

Despite trying to defend its currency, the central bank of Malaysia quickly ran out of foreign reserves to buy back its currency with on the international markets.

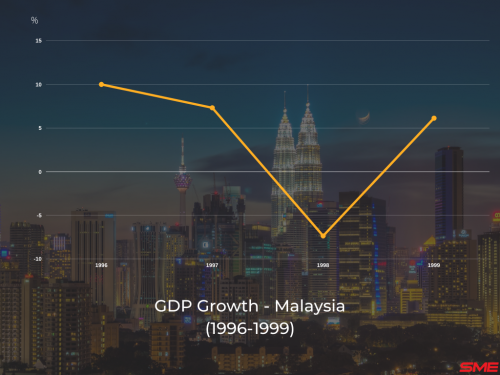

As the crisis spread, things got so bad that the currency lost half of its value alongside more than half the value of the nation’s stock exchange, swinging the economy from 10% economic growth in 1996 to over a 7% decrease by 1998.

Source: World Bank

But this is where Malaysia did something unique.

Why Was Malaysia Unique In The Asian Financial Crisis?

Unlike other severely impacted Asian economies, such as South Korea, Indonesia, or Thailand, Malaysia did not receive an IMF bailout.

This was because the country’s macroeconomic conditions were substantially stronger going into the crisis if you look at things like external debt, inflation, savings, government revenues, and even the health of its banking system.

Essentially, the country was better positioned to cope without having to resort to the harsh conditions which IMF bailouts often come with.

Another reason is because it simply didn’t agree with the typical IMF policies of cutting spending. Something it had the luxury of doing, giving it stronger financial position.

Now, whilst it initially, drastically, cut spending, it quickly changed this around. Turning on the spending taps to spend its way out of the crisis – a really unconventional move at the time and a nod to Keynesian economics.

The government had always been cautious to not penalize disadvantaged groups, stating that if the country had taken the IMF bailout, this could have impacted the poorest groups hardest as large-scale spending cuts inevitably do.

So, in order to carry off this unique approach, the country took two drastic steps.

Firstly, it prevented money leaving through capital controls and secondly, it pegged the currency against the dollar at an undervalued rate. By banning any more money from leaving the country, the nation had addressed one of the key issues of the crisis. Though to be fair, by the time it had implemented this, a lot of the money had already left.

Regarding the undervalued currency, this is something it maintained for seven years which helped exports recover by making them cheaper for other countries.

Also, by undervaluing its exchange rate, it acted as a disincentive for the remaining money from leaving the country as they would have to convert it for less than it was actually worth.

However, these policies, did come under criticism. Preventing money leaving a country and undervaluing its exchange rate didn’t exactly make it an attractive investment destination. Though to be fair, Malaysia didn’t use capital controls as the end goal – think of them more as providing the economy breathing space to carry out structural reforms.

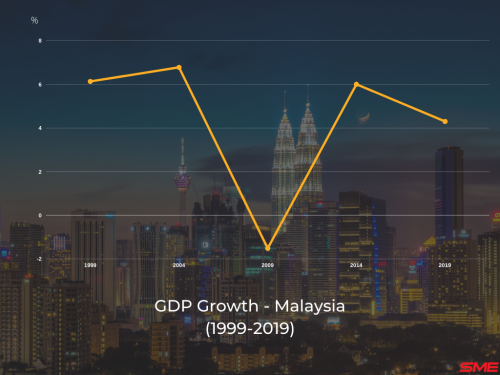

Now, the Asian financial crisis can be seen as a turning point for Malaysia. Since then, the economy has grown, producing some solid performances but, just not by enough to excel it into high income status, a goal previous government had been targeting by 2020.

Source: World Bank

This raises an important question.

Has Malaysia Become Stuck In The Middle Income Trap?

The middle income trap is a term often used to refer to countries which gets stuck within a certain income range, where incomes level off before reaching the much prized high income status.

Who decides these levels?

Well whilst there are different benchmarks, the most common is the World Banks. Every year the world bank adjusts its categories of what constitutes as low, lower middle, upper middle, or high income.

An economy stuck in the middle income trap, typically has stalled before reaching its full potential. Though the middle income trap is notoriously difficult to exit.

Only 9 out of 167 economies in a 2010 sample had moved to high income status in the previous 40 years and for context, Malaysia first entered upper middle income status in 1979.

Now, you may be wondering in that 2010 study how many of those economies were closer to higher income status than Malaysia at the start. And to be fair, the answer is 7 out of the 9, all of which were European economies.

Just 2 out of the 9 economies which made high income status in that 40-year window had a lower average income than Malaysia at the start.

Interestingly, these were both Asian economies, South Korea and Taiwan, both taking 15 years between reaching upper middle income and high income status.

Yet, on the face of it, both those economies plus Malaysia, are exporting focused, leveraging similar initial economic advantages to develop.

What Is Malaysia’s Missing Ingredient?

If we could point to one thing, it would be productivity growth. In theory, a middle-income trap means productivity has slowed down as the gains from cheaper labor and imitating foreign technology diminish.

Basically higher wages erode competitiveness. So greater levels of productivity are required to maintain growth.

And the data suggests that Malaysia’s total factor productivity growth was lower than that of both Korea and Taiwan at 0.8% relative to about 1.7% between 1970 and 2010.

Now, one way to achieve higher productivity, is through innovation. Innovation can be measured a number of different ways. Though, one way is to look at the number of patents filed by a country. This chart shows that Korea, a patent powerhouse and Taiwan both register way more patents than Malaysia.

Source: World Bank

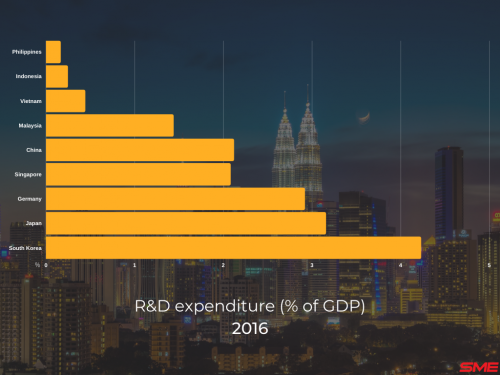

A similar picture emerges if we were to look at research and development spending as a percentage of GDP.

A world bank report found that although Malaysia doubled its research and development expenditure to 1.4% in the decade 2016, it has since declined.

For comparison, Singapore and China spent more than 2%. Japan and Germany more than 3% and South Korea really out there at almost 5%

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics

One reason for this, is that whilst Malaysia has attracted multinational corporations to help turn it into an exporting economy, the technology has not been passed on and supporting local industries developed to the same extent as other economies.

Both Korea and Taiwan ensured knowledge transfer and supporting industries were ready to advance. Likewise, neighboring Singapore pursued much more aggressive local business support and technology creation.

A great example of this, is Malaysia’s high position in the ease of doing business index, ranking 12th in the world. A solid score reflecting an attractive environment for multinational corporations to invest in.

However, taking a deeper dive into how this is calculated, shows that the score is skewed by certain factors.

Malaysia ranks 2nd in the world for dealing with construction permits and protecting minority investors which are great things if you are a large international company. But, when it comes to actually starting a business, it ranks 126th in the world.

Like many emerging market economies, the nation has also faced its fair share of scandals such as the 1MDB scandal which highlighted corruption and brought down a government.

Yet, saying all of this, the country still has a bright future. Recent government initiatives are in place to expand local industries to address this gap and to raise innovation, particularly, in the economic hotspot of Penang, a traditional powerhouse for the Malaysian economy.

There is also a drive to diversify the economy with a focus for enhancing its tourist sector and making the nation a hub for Islamic finance.

Interestingly, the country possesses a tax haven just off the North Coast of Borneo, going a long way since becoming independent.

So overall, we have seen that Malaysia has developed an industrialized base from a very low starting point, going on to adopt a unique approach to the Asian financial crisis, which reflects the capability of its institutions to reform, yet the nation has become stuck in the middle income trap for decades, something linked to low productivity growth and innovation.

However, the nation is still set to achieve high income status in the medium term, reflecting a remarkable journey and if it can overcome its productivity challenges, who knows how high it can go.