What time in human history do you think coincided with the greatest economic recovery? The answer, 100 years ago, the aftermath of world war one led to the roaring 20’s, particularly, in the United States.

As the nation’s wealth doubled, the consumer society became mainstream and mass production really kicked off. Yet, that didn’t end well. The Dow Jones stock market index crashed nearly 90% between 1929 and 1932. Unemployment skyrocketed and ultimately led to the Great Depression.

So what about the period following world war two? This was a time often called the Golden Age of capitalism as global output reached its pre-war level by 1947, strongly back of the U.S. but even Germany and Japan reached theirs by the mid-1950’s.

In fact, across the world, both developed and developing countries experienced growth rates of more than 5% on average, well into the 60’s. Rates which many would absolutely love to have today.

Crucially, it wasn’t just obscure terms like total output or GDP that improved. You can look at a wide range of metrics from employment to debt to the level of household consumption.

And whilst there will always be exceptions in both countries and metrics, the general picture was one of a strong post-war recovery. But what about recoveries not caused by global conflict?

Well, here we have many examples, including the time following the 70’s oil crisis, the 97 Asian financial crisis, the dot-com bubble of 2001, and of course the great financial crisis to name just a few. All of these events were marked by a catalyst of differing origins followed by recoveries of varying durations, which leads us on to the dramatic events of 2020.

A year which broke all sorts of economic records for the wrong reasons. Focusing on the United States for a moment, unemployment skyrocketed from 3.5% to an all time high of 14.8% in just two months.

Source: US Bureau of Labour Statistics

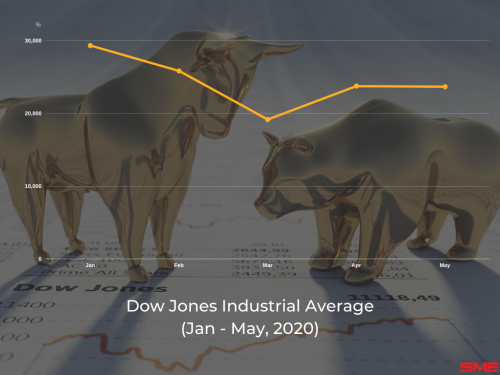

The stock market at its worst fell 35% in a month.

Source: Google Finance

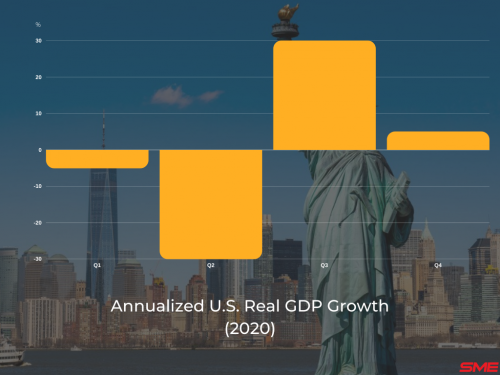

With GDP crashing by a third in the second quarter.

Source: U.S. Bureau Of Economic Analysis

Globally, 2020 is have estimated to have pushed an additional 95 million people into extreme poverty. And things in the U.K. were so bad, the crisis was dubbed the worst recession since the great frost of 1709.

Now, given these dire figures, it’s understandable that economists would make dire predictions. The problem is that these forecasts are changing more quickly and dramatically than perhaps ever before.

How Have These Forecasts Changed?

Well, let’s start with the health of the global economy before the great lockdown. The IMF predicted in their January 2020 outlook, that the world economy would grow by just over 3% continuously for the next two years.

Economic headlines were preoccupied with ongoing trade disputes and geopolitical tensions, with the report describing growth modest.

Fast forward four months and in the middle of a full-blown lockdown, the revise estimates unsurprisingly showed a dramatic 6% decline in output.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

Though, what happened in the late Autumn took the vast majority of economists, analysis, and business owners by surprise. And surprise really appears to be the best word to use here.

Taking a look at the surprise index which measures the difference between economic expectations and reality, shows a massive increase in late 2020. An upswing even greater than the initial downturn.

Source: Citi, Bloomberg, BCG Center for Macroeconomics

What’s interesting is that if you take out China, the upwards surprises become much larger for both the U.S. and Europe, meaning both the speed and scale of recovery have been unexpected.

This raises an important question.

Why Was There Such A Difference Between Expectations And Reality?

In contrast to thinking at the beginning of the crisis, the world economy is recovering faster than expected. Unemployment in most major markets is now in a downwards trend and has been for some time.

To say asset prices performed well would be an understatement. Global stock markets have not only recovered but in many cases reached new highs. If you were to look at the housing market in isolation, you would be forgiven for thinking everything was more than okay.

But such rises in asset prices have been generating a lot of fears about excess money printing and inflation.

Results like these really drive home the question of why there was such a big divergence between expectations and reality. A big reason why that was because going into the lockdown, a lot of forecasters brought in ideas from the last global recession when economies took much longer to recover.

Why?

This has a lot to do with the key elements behind economic recessions, something highlighted by Harvard Business Review.

First, there is the nature of the recession. The recession’s nature determines the recovery as much as the cause. In 2008, this was a financial crisis with an investment bust. Meaning that a lot of excess investment which had gone bad had to be paid off first, delaying and weighing down on the recovery process.

It’s hard to grow when you are still paying off five mortgages in negative equity. Contrast this with the great shutdown, which was supply side initiated as China’s factories halted production and then the rest of the world quickly followed suit.

The second element of recession is the policy response. With the benefit of hindsight, governments and central banks were criticized heavily after 2008 for not acting quick enough to address the economic concerns.

A mistake many were keen to avoid this time around. So the speed scale and effectiveness of governments responses took many by surprise. Something no better highlighted by the billions spent on stimulus checks, job retention schemes, and business loans.

Alongside the rule changes which prevented evictions and slowed down bankruptcies. This extreme form of government intervention has another benefit which leads us on to the third element of our recession, structural damage to the economy.

The unbelievable scale of government interventions prevented significant harm to the productive capacity of economies around the world. A great example of this is the retention of workers as mentioned earlier.

By doing so, economies limited long-term unemployment and the associated loss of these workers skills. Meaning that when things started to open back up, retaining workers meant more businesses were ready to go.

But all this policy response, notably, the spending has led to some concerns. One which has been highlighted more than most is the risk surrounding inflation and with a good reason.

The number of dollars in existence increased by a staggering 40% in 2020 alone. Being the direct consequences of unprecedented federal spending which helps explain our difference between economic expectation and reality.

Whilst rising prices are still working their way through the official basket of goods countries are using to calculate inflation, the world has already experienced a strong divergence between asset markets for things like stocks, houses, and until recently cryptocurrencies, and the rest of the economy.

As it turns out, printing massive amounts of cash without massive amount of new goods is generally accepted to lead to higher prices which are projected to increase above target inflation rates for a while yet.

What Are The Future Recovery Projections?

Here is where the devil is really in the details. On the surface, a stronger recovery than any time during the crisis is being predicted.

The United States alone, is expected to reach its pre-2020 peak before the end of 2021 and the Eurozone shortly afterwards.

This sounds great, though, digging a little deeper, suggests we are actually seeing the emergence of a multi-speed recovery across the world. This can be witnessed by taking a look at the differences in expected growth between just before the crisis and today, with some regions expected to do far better in the longer term than others.

Notably, all regions except for the United States, are expected to experience less growth than previously thought up until 2024. However, the scale of the setbacks really do vary.

In general, those countries which had the luxury of deploying the largest stimulus plans and access to the best healthcare, such as advanced economies, are expected to suffer relatively less than the emerging markets of Asia and Latin America – reinforcing the idea of a two-tiered recovery, at least when it comes to the very crude measure of economic output.

For all the talk of a recovery, the answer is both yes and no. This isn’t a straightforward question and to be honest, was never meant to be.

There are certain segments of the global economy which have rebounded, then, there are others which are just starting to and yet still others which may never fully. There are regions, countries, and sectors which tick the box and those which are still a long way off.