The Thai economy is the second largest in Southeast Asia. Being right in the center of one of the most vibrant economic clusters on the planet famous for its sun, sand, and sea, Thailand is so much more than just a tourist hotspot.

We are going to discuss Thailand’s overall economic journey, not just more recent events.

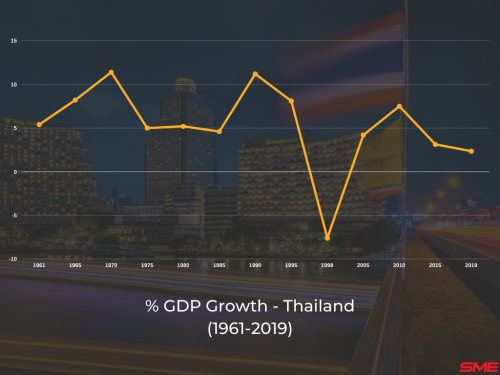

The nation went on an incredible growth run in the second half of the 20th century. However, economic growth has been trending downwards since, leading some to suggest Thailand’s economy is stuck in the middle-income trap.

Source: World Bank

So, what are the factors behind this in Thailand’s case? How did a scheme to increase rice production impacts the economy? And what is Thailand pinning its economic hopes on?

As always, to understand an economy today, it’s vital to get a sense of its history.

How Did Colonialism Impact Thailand Without Being A Colony?

Thailand is fairly unique in being the only country in Southeast Asia to avoid direct colonial rule excluding the areas actually invaded.

You see, back in the 19th century, Thailand or as it was known then, Siam, was virtually surrounded by British colonies to the West and South and French ones to the North and East, being a buffer state to both empires.

However, this certainly didn’t mean the colonial powers weren’t influential, particularly when it came to trade.

In 1855, Thailand signed the Bowring Treaty with Great Britain, which basically meant tariffs were kept to 3% or below. Similar treaties were quickly made with other colonial powers, though, it’s important to point out that such treaties should not be mistaken with the free trade agreements we have today.

The terms were very much geared to extracting natural resources and importing expensive machinery, at the expense of any domestic competition.

These treaties became even more important after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 which sharply increased trade particularly for rice. It’s estimated that rice exports increased 25-fold between 1850 and the 1930s with the nation comprising about a third of the world trade.

This agricultural focus on exports was reflective of the wider economy being heavily dependent on this sector. Despite the low tariffs, many argue that poor trade terms stifled domestic industry and deprived the government of revenues.

Counter-intuitively, such an open trade regime meant that whilst Thailand ran a trade surplus, its domestic market remained pretty stagnant.

One very good reason for this was that a significant proportion of profits weren’t reinvested locally, but sent abroad. This profit leakage was partly due to foreign companies repatriating profits.

However, by skipping over a lot of history here, the second world war saw the decline of the old trading houses.

A period of radical change followed, which helped the domestic economy to really start growing as we are about to find out.

How Did Thailand’s Economy Take Off?

By the late 1940s, the economy was still one based on agriculture, particularly rice cultivation, which accounted for an estimated 25% of GDP and half of exports.

As we have discussed in other articles, a post-war emphasis was placed on rapid industrialization, achieving a great deal of economic growth through structural transition from low productivity agriculture to higher productivity industry.

Yet, it’s worth noting that land reform was not as far-reaching or effective as other nations who rapidly industrialized.

The UN reports that only a quarter of farmers have irrigation, with average farming plots fairly small, limiting economies of scale, and investments in capital.

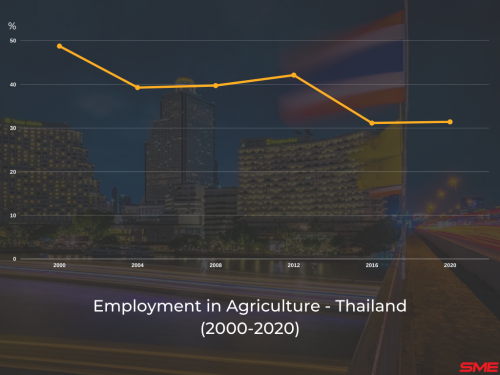

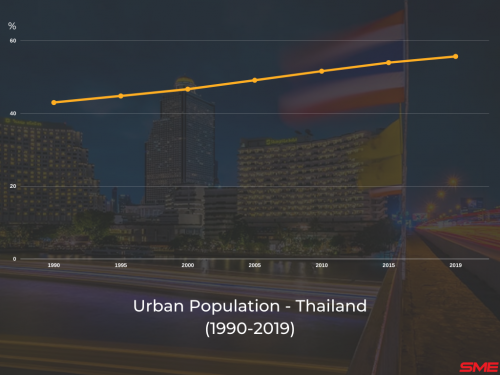

Today, around 30% of the workforce are still employed in agriculture with the nation reaching the important milestone of becoming a majority urban country in 2018.

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

Now, tracking back to how Thailand industrialized at the start.

By the 1960s, an attractive idea that was doing the rounds amongst pretty much anyone who would listen, was import substitution.

As usual, in theory, this was a great idea yet the reality was completely different. Thailand’s relatively small domestic market meant the strategy was ditched – being replaced with one favoring export-oriented growth.

So, focusing on export-led growth with a bit of help from comparative advantage helped the country raise its income. Importantly, in Thailand’s case, macroeconomic stability in the decades following world war two was crucial.

Now, this economic stability was largely the result of the setup of Thai governance which was a hangover from beliefs from the colonial era that financial failures risked foreign intervention. A point we will come back to in a minute.

You see, economic governance was largely separate from politics. Technocrats ran day-to-day economic affairs and set a lot of the rules. Though, to be fair, more recent times have seen this separate technocratic governance fade.

As we have discussed before, the 80s and the early 90s were in general a period of rapid growth for the region. Thailand was no exception, experiencing some of its best growth during this period.

As part of a macroeconomic stability strategy, the Thai currency was pegged to the dollar. However, as the economy grew, credit exploded with vast sums of foreign capital pouring into the market.

From the outside, the fundamentals looked strong. Though, rumors started to circulate over just how stable the system actually was.

By 1997, the Thai currency had come under increasing attack to abandon its currency peg. With the central bank’s reserves quickly being depleted, it resulted in a forced free float and an IMF bailout.

Ultimately, the crisis-induced reforms, and a much more competitive exchange rate which was floating, led the nation to export its way out.

Though, to be fair, Thailand like many countries, has been criticized for currency manipulation featuring on a watch list of currency manipulators.

So, with the historical aspects covered, it’s time to consider the economy of Thailand in more recent years, one often associated with tourism.

Is Thailand’s Economy More Than Just Tourism?

Thailand, for a lot of people is closely associated with tourism and for a very good reason. Bangkok was routinely the most visited city on earth before the pandemic, accounting for roughly a fifth of both GDP and employment, a vital source of foreign currency.

Its lockdown induced collapse in 2020 and the tourism sector was hit bad. Looking at the Asean-5 Real GDP as of April 2021, it’s easy to say Thailand recovery is slow as compared to other nations in the region.

Source: IMF

However, in saying all of this, Thailand is much more than just tourism. Putting down your beach towels for a second or more, likely a year plus, it has a substantial manufacturing sector which accounts for a third of GDP.

Electronics and store production are large industries, but car manufacturing is a flagship industry. It’s become some sort of Detroit of Asia, one in its prime of course.

What the nation does well is provide the car parts and assembly hubs for most major car brands, with this sector accounting for roughly 10% of GDP.

Yet, this doesn’t hide the fact that Thailand’s economic growth has slowed down considerably long before 2020.

Why Has Economic Growth Trended Downwards?

A slowdown in growth is natural as an economy develops. Though Thailand has routinely underperformed its benchmark in recent years, don’t get us wrong, incomes have on average been rising.

For example, the country reached upper income status in 2011. Yet, given the inputs available, economists were anticipating just a little bit more, suggesting that certain factors are dragging on growth.

Here is where similarities with Malaysia for example can be drawn. Both countries suffer from low productivity. In Thailand’s case, a strong source of historic productivity gains has seen the sector shift from agriculture to manufacturing.

Though, this is a short-term strategy, as once the shift is made, the initial boost fades away. Less than half of the labor force has primary schooling, through no fault of their own.

But, what this means in practice is that low-skilled productivity employment, whether that be tourism or agriculture, is a big employer.

Another factor is Thailand’s declining rate of Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Directed appropriately, FDI can certainly stimulate an economy, and in the right context facilitate the transfer of knowledge.

For a country which is still urbanizing, this can be a huge win. In truth, there is rarely one reason why FDI would decline. Though in recent years growing concerns of a trade war between two of its largest trading partners hasn’t helped nor has political instability, something we are definitely going to be touching on later in this article.

According to the world bank’s political stability index, Thailand ranked 142nd in the world between Brazil and Russia. Interestingly, the top-ranked country on this index was Iceland. Pretty cool for a country based on an active volcano.

Foreign investment has also been hampered longer term by legislation. Take the ownership of land, which is notoriously restricted, not to mention the foreign business act which effectively places sectors into categories with harsher restrictions for industries deemed more worthy of protection.

Though to be fair, the list isn’t static and moves have been made to liberalize. But, it still doesn’t help the investment climate.

Now, when discussing productivity and investment, it’s hard to avoid the role of Thailand’s state-owned enterprises which in excess can often be taken as a red flag for non-competitive practices.

In 2010, they accounted for an estimated 32% of GDP and five years later 40%. So yeah, they are a pretty big deal. Frequently expanding at a faster rate than the Thai economy itself.

It’s worth noting that these mega corps focus mainly on the provision of public services. Think electricity, telecoms, and transport.

What’s most interesting about these organizations though is that on average, they make a profit.

But why?

After all we have mentioned numerous times on numerous articles how eventually industries have to become competitive to be sustainable in the long run.

Well, there are three main reasons. Firstly, they are often monopolies, so can charge monopolistic rents. Secondly, they are granted preferential treatment in procuring goods and services. Thirdly, where necessary, the government provides cheap loans or just straight up cash, plus, there’s a useful loophole that if they are not incorporated, they pay no corporation tax, instead, they are treated as a department of the state.

Though this does come with making contributions to the state treasury, contributing over 5% of all state revenue in recent years. We never said they’d get a free lunch.

Sticking with the theme of government, we stated earlier how political instability can weigh on an economy and depending on who you ask, Thailand has had about 13 coups in about 80 years, putting it at or near the top worldwide.

The truth is though, the exact number is unknown, as many failed coup attempts go unreported.

Talk about the political landscape can often give us a good insight into why economic strategies are pursued.

Why Have Populist Policies Not Always Worked Out?

Whilst all countries have their fair share of questionable policies, it’s worth highlighting two of Thailand’s. And for balance, we will also be mentioning some of their more positive policies afterwards.

One of the questionable policies was Thailand’s rice pledging strategy between 2011 and 2014. This seems like a long time ago but it had far reaching consequences. Essentially, the strategy was to offer money to farmers in exchange for their rice or a rice pledge.

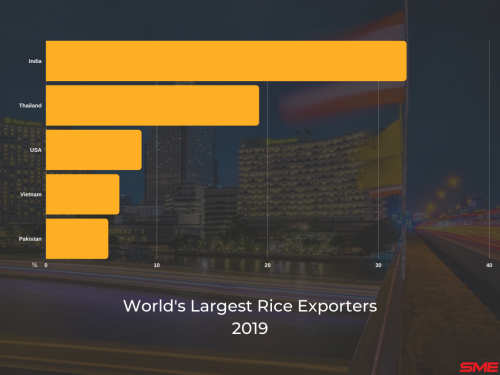

Source: International Trade Center

You can see the appeal, Thailand is the world’s second largest rice exporter with a third of its workforce based in agriculture. So, it sounds simple enough.

The trouble though, was that the price offered to farmers was way above the market rate, up to 50% above. With massive uncapped uptake, at the start, this ended up costing well over 15 billion dollars, an amount not expected to be paid back for another eight years, according to Thailand’s debt management office.

Even going so far as to be cited as a credit rating risk factor. And of the many reasons for the 2014 military coup.

Sadly, critics claim it also hasn’t spurred on rice productivity, with Thailand notoriously lagging in this sector. To be fair though, increasing incomes for an often marginalized group such as farmers is a policy within itself, just an extremely expensive one in this case.

Another great idea on paper was Thailand’s first time car buyer scheme. The basic idea behind it was to kick-start domestic consumption of cars in a country which we has discussed already, produced a lot of cars.

The only problem was that higher consumption of cars wasn’t sustained, again not something unique to Thailand with the country also launching schemes to stimulate demand since.

Now, so far we have discussed a number of challenges and issues facing the Thai economy. But what is the economy plan?

To Build The Economy

Something called Thailand 4.0. It represents the next stage in growth. Stage 1 was Agriculture, Stage 2 Light Industry, and Stage 3 Advanced Industry with Stage 4 being all about Tech and Innovation.

In fairness, the plan is aimed at addressing some of the challenges we mentioned earlier. Targeting productivity, wealth inequality, and human development.

Key to acting on this plan is Thailand’s new economic growth hub. Starting with the East Economic Corridor. A corridor which covers 13,000 square kilometers across the bay of Thailand. The plan being, to turn the area into a tech manufacturing and services hub with strong connectivity by land, air, and sea.

Infrastructure development and job creation are also fundamental. Think high-speed rail, better roads and airport expansion.

However, a key way of funding this is by offering tax breaks to foreign firms and workers which economists have questioned, primarily whether this truly addresses the nation’s investment barriers, with lingering concerns regarding bureaucracy stability and high perceived levels of corruption, noting that Thailand ranks 101st in the world according to the corruption transparency index.

Whether Thailand can address these issues, will be just as important as anything they build.

So overall, we have seen that Thailand has a unique history, though not escaping the influence of the powers of the time.

Agriculture has and to some extent still is a large part of economic reality which is despite a strong process to industrialize and substantial services sector albeit one skewed towards tourism, which is crucial to Thailand, as the economic fallout of 2020 proved, but, by far not the only sector.

The trend down in economic growth is attributable to a variety of factors including legislative barriers to investment, the dominance of state-owned enterprises and poor productivity.

At times, questionable policies have been adopted. Though, to be fair, Thailand is far from alone in this regard.

Its Thailand 4.0 strategy, is testament to a country looking to the future and let’s not forget the country has made significant progress.

Thailand has a lot going for it. One such anticipation is the proposed Thai Canal project, a huge mega project which would be a game changer not just for Thailand but the entire continent and beyond.